· today in space history · 5 min read

The Day America Entered the Space Age

Sixty-seven years ago, a slender rocket carried America's first satellite into orbit, discovering a mysterious feature of our planet that would change our understanding of space forever

In the predawn hours of February 1, 1958, a modified Jupiter-C rocket stood gleaming on Launch Complex 26A at Cape Canaveral. Inside its nose cone sat Explorer 1, a slender cylinder just 80 inches long and 6 inches in diameter that would soon make history as America’s first satellite. What began as a response to the Soviet Union’s Sputnik launches would end up transforming our understanding of Earth’s space environment forever.

A Milestone in Spacecraft Design

Explorer 1 itself was a triumph of minimalist engineering. Weighing just 30.8 pounds, of which 18 pounds was scientific instrumentation, it was a fraction of the size of Sputnik 1’s 184 pounds. The satellite’s instruments were powered by mercury chemical batteries that made up nearly 40% of the payload weight, providing 60 watts to run its experiments and radio transmitters.

The spacecraft’s exterior was carefully designed for its mission. Its stainless steel body was sandblasted and painted with white stripes – a pattern chosen after careful study of shadow-sunlight intervals based on the planned trajectory. Two sets of antennas handled communication: a 60-milliwatt transmitter connected to dipole antennas embedded in the satellite’s body, and a 10-milliwatt transmitter feeding four whip antennas that formed a turnstile configuration.

The Historic Launch

At precisely 03:47:56 GMT, the Jupiter-C’s engines ignited. The rocket, officially designated Juno I for this mission, performed flawlessly through all four stages. The launch team had to wait longer than expected for confirmation of orbital success – the satellite had actually achieved a higher orbit than planned, with a perigee of 358 kilometers and an apogee of 2,550 kilometers.

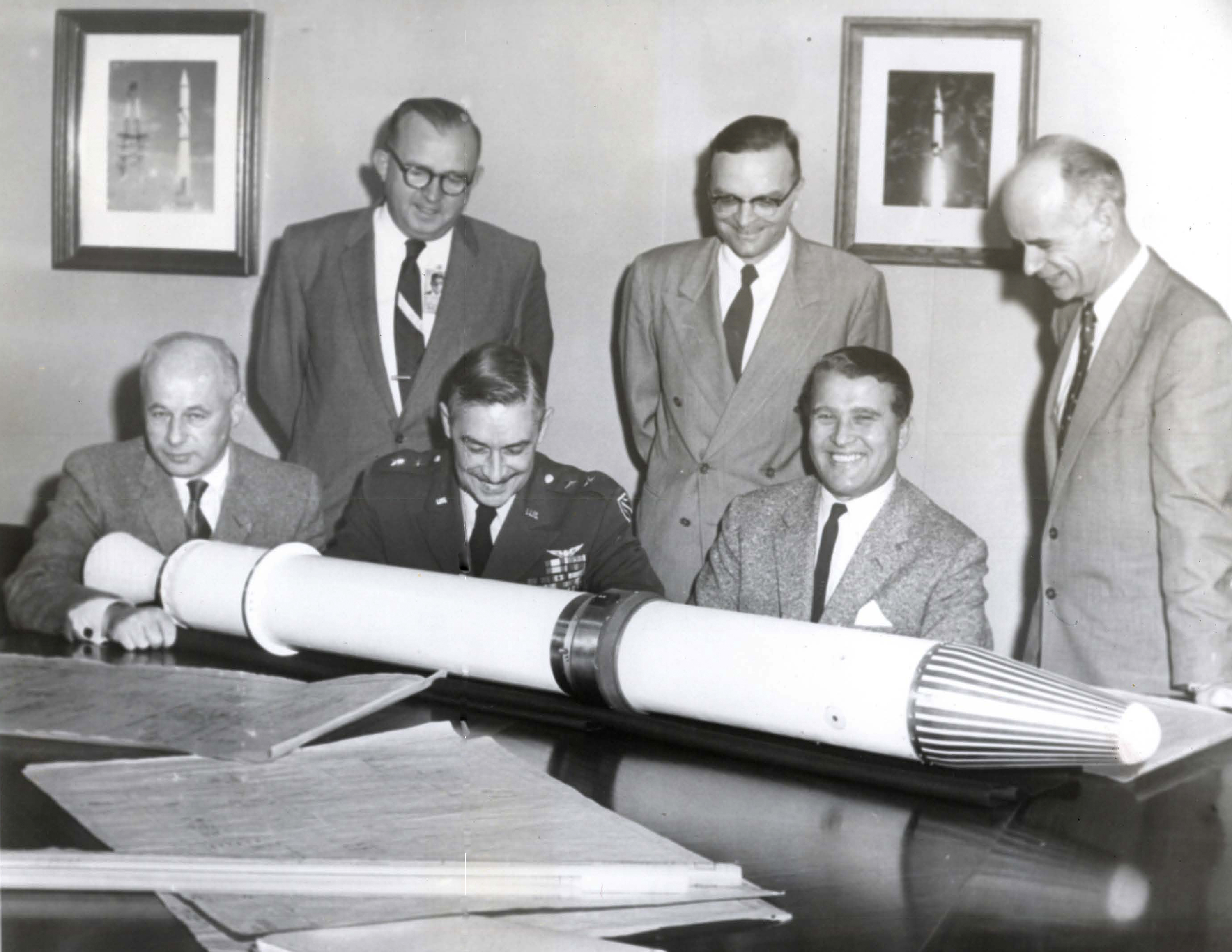

When news of success finally came at around 06:30 GMT, a hastily arranged press conference at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. announced America’s entry into the Space Age. The satellite’s orbit would last far longer than its planned three-month mission, continuing until March 31, 1970, completing over 58,400 orbits of Earth.

An Unexpected Scientific Revolution

Explorer 1’s most famous discovery came from a puzzling pattern in its data. The satellite carried a sensitive Geiger-Müller tube designed by Dr. George Ludwig at the University of Iowa to detect cosmic rays. The instrument showed normal cosmic ray counts at lower altitudes but mysteriously registered zero counts at higher altitudes over South America.

Dr. Van Allen and his team eventually realized that rather than instrument failure, these readings indicated radiation levels so intense they overwhelmed the detector. This was the first evidence of what we now call the Van Allen radiation belts – zones of energetically charged particles trapped by Earth’s magnetic field.

The satellite also carried other instruments: five temperature sensors, an acoustic detector for micrometeorite impacts, and a wire grid detector. The micrometeorite detector recorded 145 impacts during its operational period, allowing scientists to calculate the first accurate estimates of cosmic dust concentrations in near-Earth space.

The Hidden Heroes Behind the Launch

While the names of Wernher von Braun, William Pickering, and James Van Allen would become famous for Explorer 1’s success, the mission’s calculations depended on a remarkable team of women computers at JPL. Barbara Paulson and her colleagues worked tirelessly through the night of January 31, plotting data from tracking stations to confirm the satellite’s orbit. Using nothing but pencils and graph paper, these human computers calculated the complex trajectories and orbital parameters that would guide Explorer 1 into its historic flight.

Their calculations had to be perfect – the smallest error could mean the difference between orbit and failure. The women’s work was so trusted that even as mechanical computers became available, many engineers preferred their hand-calculated results. This was engineering at its most fundamental level, requiring deep understanding of orbital mechanics and meticulous attention to detail.

Engineering Lessons Learned

The mission also provided unexpected insights into spacecraft dynamics. Engineers had designed Explorer 1 to spin about its long axis, but the satellite instead began to precess due to energy dissipation from its flexible elements. This behavior led to the first major development in rigid body dynamics theory since the work of Euler nearly 200 years earlier, as scientists worked to understand how momentum-preserving energy dissipation affects rotating bodies in space.

Legacy for Modern Spaceflight

Today, understanding the Van Allen belts remains crucial for satellite operations and human spaceflight. Modern spacecraft must be designed with radiation-hardened electronics to withstand these harsh conditions, and mission planners carefully consider the belts’ location when designing orbital trajectories.

The success of Explorer 1 also established several enduring principles of space exploration: the value of lightweight, efficient design; the importance of thorough ground testing; and the power of combining basic research with technological achievement. The mission launched the Explorer program, NASA’s longest-running spacecraft series, which continues to make discoveries about our solar system and universe.

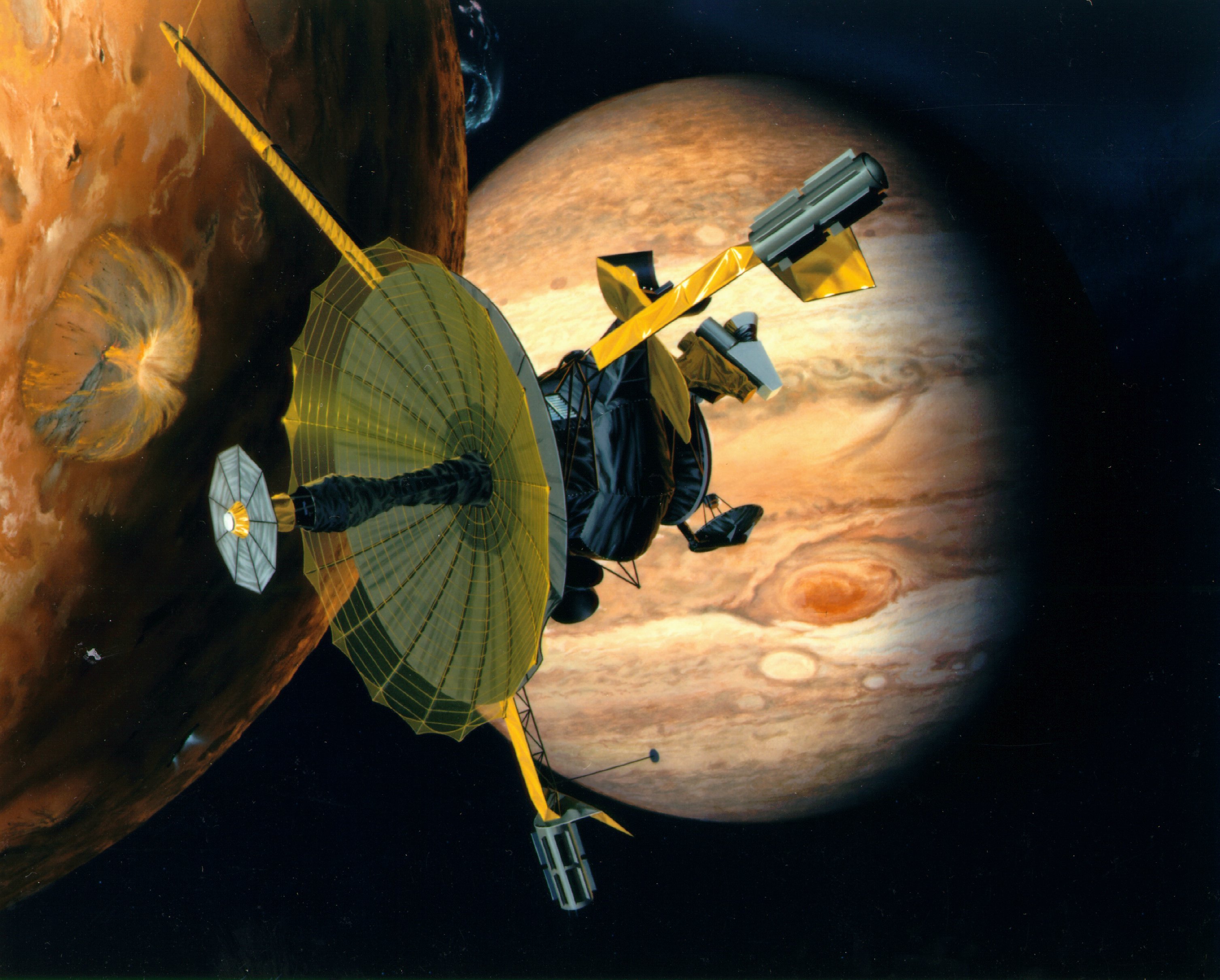

The human computers who supported the mission helped establish a tradition of excellence in spacecraft navigation and orbital calculations that continues at JPL today. Sue Finley, hired in 1958 to work on trajectory computations, remains NASA’s longest-serving female employee, currently working on missions to Jupiter – a living link to that historic February morning when America first reached space.

While Sputnik 1 may have been first in space, Explorer 1 demonstrated that scientific discovery, not just technological achievement, would be the true measure of success in space exploration. Its mission reminds us that even in the midst of political competition, the pursuit of scientific knowledge can yield unexpected discoveries that benefit all of humanity.

Theodore Kruczek