· today in space history · 4 min read

The Day Earth Became a Pale Blue Dot

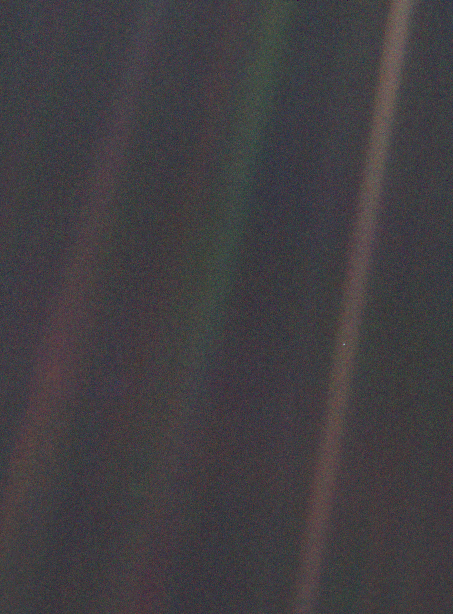

Thirty-five years ago, Voyager 1 captured a revolutionary series of images from the edge of our solar system, forever changing how humanity sees its place in the cosmos

At 04:48 GMT on February 14, 1990, from a distance of 6.4 billion kilometers, NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft began a historic photography session that would transform humanity’s perspective of its cosmic home. Over the next 34 minutes, the spacecraft’s narrow-angle camera captured a series of 60 images that would become known as the Family Portrait, including the iconic Pale Blue Dot photograph showing Earth as a mere pixel in the vast cosmic dark.

A Daring Last Look

The Family Portrait sequence represented a significant technical challenge. By 1990, Voyager 1 was operating at the extreme edge of its capabilities. Its primary mission to Jupiter and Saturn long complete, the spacecraft was racing toward interstellar space at 64,000 kilometers per hour. To capture these final images, controllers had to precisely aim Voyager’s camera platform, even though Earth appeared smaller than a single pixel in its field of view.

Engineering at the Edge

Voyager 1’s imaging system was pushing its absolute limits. The spacecraft’s narrow-angle camera, with its 1500mm focal length telescope, was designed for close-up planetary encounters, not for capturing faint points of light across astronomical distances. The exposure times had to be carefully calculated to collect enough light while compensating for the spacecraft’s motion. Each image required 0.72 seconds of exposure time, during which Voyager had to maintain perfect stability despite being billions of kilometers from Earth.

The Portrait Session

The imaging sequence captured six of the planets: Earth, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Mercury was too close to the Sun to photograph, and Mars was obscured by scattered sunlight in the camera optics. The images were taken using three color filters and required the spacecraft to make 39 separate pointing maneuvers. Each image was encoded into digital data and transmitted back to Earth at 1,400 bits per second through NASA’s Deep Space Network.

A Pixel-Sized Perspective

Among these images, one frame would become particularly famous. In the photo showing Earth, our entire planet appears as a pale blue dot just 0.12 pixels in size, caught in a ray of scattered sunlight. This image, championed by astronomer Carl Sagan who had proposed the photo sequence, would become one of the most influential space photographs ever taken.

Technical Achievement, Philosophical Impact

The Family Portrait sequence marked several technical milestones. It represented the most distant photographs of Earth and the planets ever taken at that time. The images required sophisticated processing at JPL to remove scattered sunlight and enhance the barely visible planets. But perhaps more significantly, these technical achievements served to deliver a profound philosophical message about humanity’s place in the cosmos.

Legacy in Space Exploration

After completing the Family Portrait, Voyager 1’s cameras were permanently powered down to conserve energy for its continuing journey into interstellar space. The technique of capturing wide-field planetary system portraits would later be repeated by other spacecraft, including Cassini’s image of Earth from Saturn in 2013 and New Horizons’ image from beyond Pluto in 2020.

Looking Forward

Today, as new space telescopes peer deeper into the cosmos and rovers explore Mars, the Pale Blue Dot remains a powerful reminder of perspective. As humanity prepares for new journeys to the Moon and Mars, Voyager 1’s Family Portrait continues to influence how we think about our place in space. The spacecraft itself, now in interstellar space, carries these images encoded in its computer memory as it ventures further into the unknown, a testament to human ingenuity and our eternal quest to understand our place in the universe.

The technical achievement of capturing these images from such an immense distance, combined with their profound impact on human perspective, makes February 14, 1990, one of the most significant dates in space exploration history. As Carl Sagan noted, these images showed us our world as it truly is: a tiny, fragile oasis in the cosmic ocean.

Theodore Kruczek