· today in space history · 4 min read

The Day a Farm Boy Found a New World

Ninety-five years ago, a 24-year-old astronomer with no college degree made one of astronomy's most remarkable discoveries, finding a new planet that would challenge our understanding of the solar system

On a cold Tuesday morning in Flagstaff, Arizona, February 18, 1930, a young astronomer named Clyde Tombaugh sat down at his blink comparator, continuing the methodical search that had consumed his days for nearly a year. As he flicked back and forth between two photographic plates taken of the same patch of sky in late January, something caught his eye – a tiny dot that jumped position against the fixed background of stars. In that moment, Tombaugh knew he had found what many considered impossible: the ninth planet of our solar system.

A Search Born of Mathematical Mystery

The discovery of Pluto wasn’t a chance occurrence but the result of a deliberate search sparked by a mathematical puzzle. Astronomers had noticed unexplained perturbations in the orbits of Uranus and Neptune, leading them to suspect the presence of another massive planet. Percival Lowell, founder of the Lowell Observatory, had spent years searching for this hypothetical “Planet X” before his death in 1916. The search lay dormant until 1929, when the observatory hired the 23-year-old Tombaugh, a farm boy from Kansas who had impressed them with his detailed astronomical drawings.

The Most Tedious Job in Astronomy

Tombaugh’s search method was extraordinarily demanding. Using the observatory’s 13-inch astrograph, he would photograph the same section of sky several nights apart. Each photographic plate contained tens of thousands of stars. Using a blink comparator – a device that rapidly alternated views between two plates – Tombaugh would look for any objects that changed position. The work required intense concentration and meticulous attention to detail.

“I had to examine each pair of plates three times to be sure that I had not missed anything,” Tombaugh later recalled. In the fourteen years he spent searching the skies, he would examine 90 million star images – two views each of 45 million stars.

The Historic Discovery

When Tombaugh noticed the moving object on his photographic plates from January 23 and 29, he knew he needed confirmation. Additional observations proved that the object was indeed moving in a way consistent with a planet beyond Neptune. The discovery was particularly remarkable given that the object was near the galactic plane, where the dense star field of the Milky Way made detecting moving objects especially challenging.

Naming a New World

The announcement of the discovery on March 13, 1930, sparked worldwide excitement and a flurry of suggested names. The chosen name, Pluto, worked on multiple levels: the Roman god could make himself invisible, the first two letters were Percival Lowell’s initials, and it was suggested by Venetia Burney, an 11-year-old girl from Oxford, England. The name was officially adopted on May 1, 1930.

A Complex Legacy

As more powerful telescopes scanned the outer solar system, astronomers began to realize that Pluto was not alone in its realm of space. The discovery of numerous other icy bodies in what would become known as the Kuiper Belt led to a fundamental shift in our understanding of the solar system’s structure. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union established formal criteria for planetary status, leading to Pluto’s reclassification as a dwarf planet.

Tombaugh’s widow Patricia later reflected that while he had defended Pluto’s planetary status during his lifetime, he would have understood the scientific reasoning behind the reclassification. “He was a scientist,” she noted. “He would understand they had a real problem when they start finding several of these things flying around the place.”

Looking Forward

Today, Tombaugh’s discovery is recognized not just as finding a single world, but as the first glimpse of an entirely new region of our solar system. As astronomer Hal Levison noted, “Clyde Tombaugh discovered the Kuiper Belt. That’s a helluva lot more interesting than the ninth planet.” This vast zone of icy bodies beyond Neptune has revolutionized our understanding of the solar system’s formation and evolution.

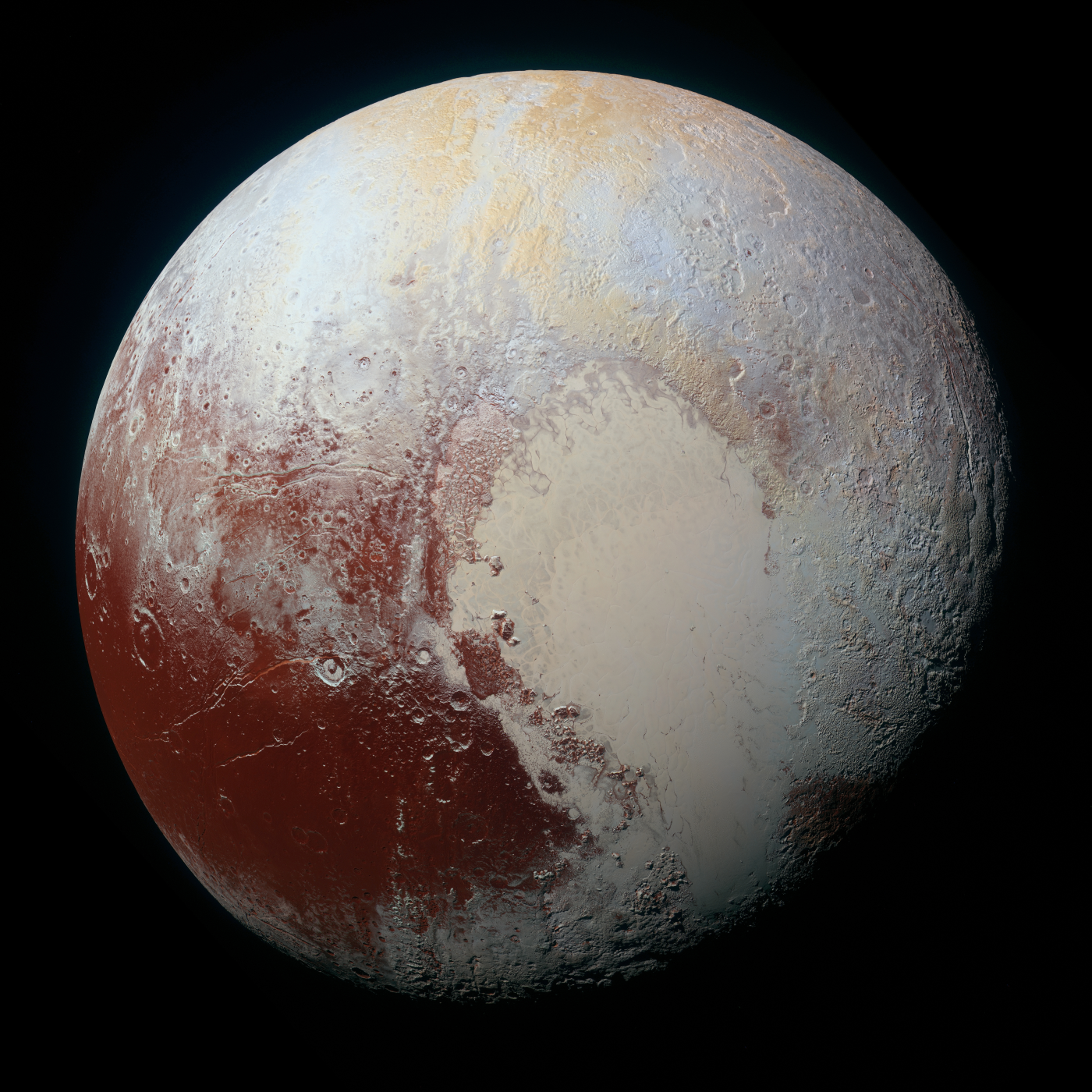

As we continue to explore the outer reaches of our cosmic neighborhood, with missions like New Horizons revealing Pluto’s unexpected complexity, Tombaugh’s meticulous search serves as a reminder that groundbreaking discoveries often come through patience, persistence, and careful observation. His work opened our eyes to the true diversity of our solar system, proving that even in an age of advanced technology, human dedication and attention to detail remain crucial to scientific discovery.

Theodore Kruczek