· today in space history · 5 min read

The Day America's Spy Satellites Gained New Eyes

Sixty-three years ago, a Thor-Agena rocket launched the first dual-camera reconnaissance satellite, revolutionizing space-based intelligence while hiding behind the final use of a famous cover name

At precisely 11:39 AM Pacific Time on February 27, 1962, a Thor-Agena rocket thundered skyward from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, carrying aloft what appeared to be just another scientific satellite in America’s Discoverer program. In reality, this launch marked a pivotal moment in space-based intelligence gathering. Discoverer 38, as it was publicly known, represented both an end and a beginning—the final use of the “Discoverer” cover name and the first deployment of a revolutionary new reconnaissance capability that would transform how America monitored its Cold War adversaries.

A Cover Story’s Final Chapter

The “Discoverer” designation had served as the public face for America’s top-secret Corona reconnaissance satellite program since 1959. This elaborate cover story portrayed the launches as scientific research missions, concealing their actual purpose of photographing denied territory from space. Discoverer 38 would be the last to carry this name. Future Corona missions would operate under deeper secrecy, with no public announcements or cover names—effectively disappearing from public view despite launching regularly from California’s coast.

Engineering a New Set of Eyes

What made Discoverer 38 truly revolutionary was hidden within its cylindrical frame. Unlike previous Corona satellites that carried a single panoramic camera, this mission—designated KH-4 (Keyhole-4) by intelligence officials—introduced a dual-camera system called “Mural.” These two panoramic cameras were positioned at different angles (15 degrees forward and 15 degrees aft) to capture stereoscopic imagery of the same terrain from slightly different perspectives.

“The stereo capability transformed our understanding of what we were seeing,” explained a former photo interpreter years later. “Before, we could see objects but struggled to determine their height. With stereo imagery, we could finally perceive depth—how tall a building was, the depth of a missile silo, or the elevation of a mountain pass.”

The Technical Achievement

The precision engineering required for the dual-camera system presented significant challenges. Each camera featured a 24-inch focal length with a sophisticated lens system that swept back and forth to cover a wide area while maintaining sharpness. The cameras used specialized 70mm film with a resolution far exceeding anything available to commercial photography at the time.

During its approximately 65 orbits, Discoverer 38 methodically photographed vast areas of interest, particularly focusing on Soviet and Chinese military installations, industrial complexes, and nuclear facilities. The satellite functioned essentially as a sophisticated space-based camera platform, capturing images that would later be analyzed by intelligence specialists to track military developments in denied areas.

The Dramatic Recovery

The most challenging aspect of the Corona program was not taking the photographs but retrieving them. As Discoverer 38 completed its mission, ground controllers commanded the reentry vehicle—a cone-shaped capsule containing the precious film—to separate from the satellite. After a precisely calculated deorbit burn, the capsule plunged into the atmosphere, protected from the intense heat of reentry by an ablative heat shield.

At approximately 60,000 feet, a parachute deployed to slow the capsule’s descent. In what resembled a scene from a spy thriller, specially modified C-119 “Flying Boxcar” aircraft patrolled a recovery zone in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii. Using a trapeze-like apparatus extending from the rear of the aircraft, recovery crews snagged the capsule in mid-air on its 65th orbit—marking the 13th successful recovery of film from space and the ninth captured in mid-air.

This aerial retrieval, performed on March 2, 1962, was necessary to prevent the film from landing in the ocean, where salt water could damage the precious intelligence imagery. It represented one of the most challenging aerial maneuvers performed regularly by military pilots during the Cold War era.

Impact on Intelligence Gathering

The imagery returned by Discoverer 38 and subsequent KH-4 missions transformed American understanding of Soviet and Chinese military capabilities. The stereoscopic capability allowed analysts to calculate the precise dimensions of sensitive facilities, weapons systems, and military deployments.

This technological leap came at a crucial time in the Cold War. Just months after the Berlin Wall had been erected and less than a year after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, American intelligence agencies were desperate for reliable information about Soviet military developments. The Cuban Missile Crisis would erupt just seven months later, during which Corona imagery would play a crucial supporting role to the lower-altitude U-2 aircraft photographs that identified Soviet missile installations in Cuba.

Legacy and Impact

The KH-4 series inaugurated by Discoverer 38 would prove remarkably successful and long-lived. Over the next decade, 26 KH-4 satellites would be launched, followed by more advanced KH-4A and KH-4B models with progressively better resolution and capabilities. Together, they would form the backbone of American space-based intelligence gathering throughout the 1960s.

The impact of this technology extended far beyond intelligence applications. The precise stereoscopic mapping of broad areas created accurate geographical information about remote regions of the world. When this imagery was declassified in 1995, archaeologists and environmental scientists discovered a treasure trove of historical data showing landscape changes, archaeological sites, and environmental conditions dating back to the early 1960s.

Looking Forward

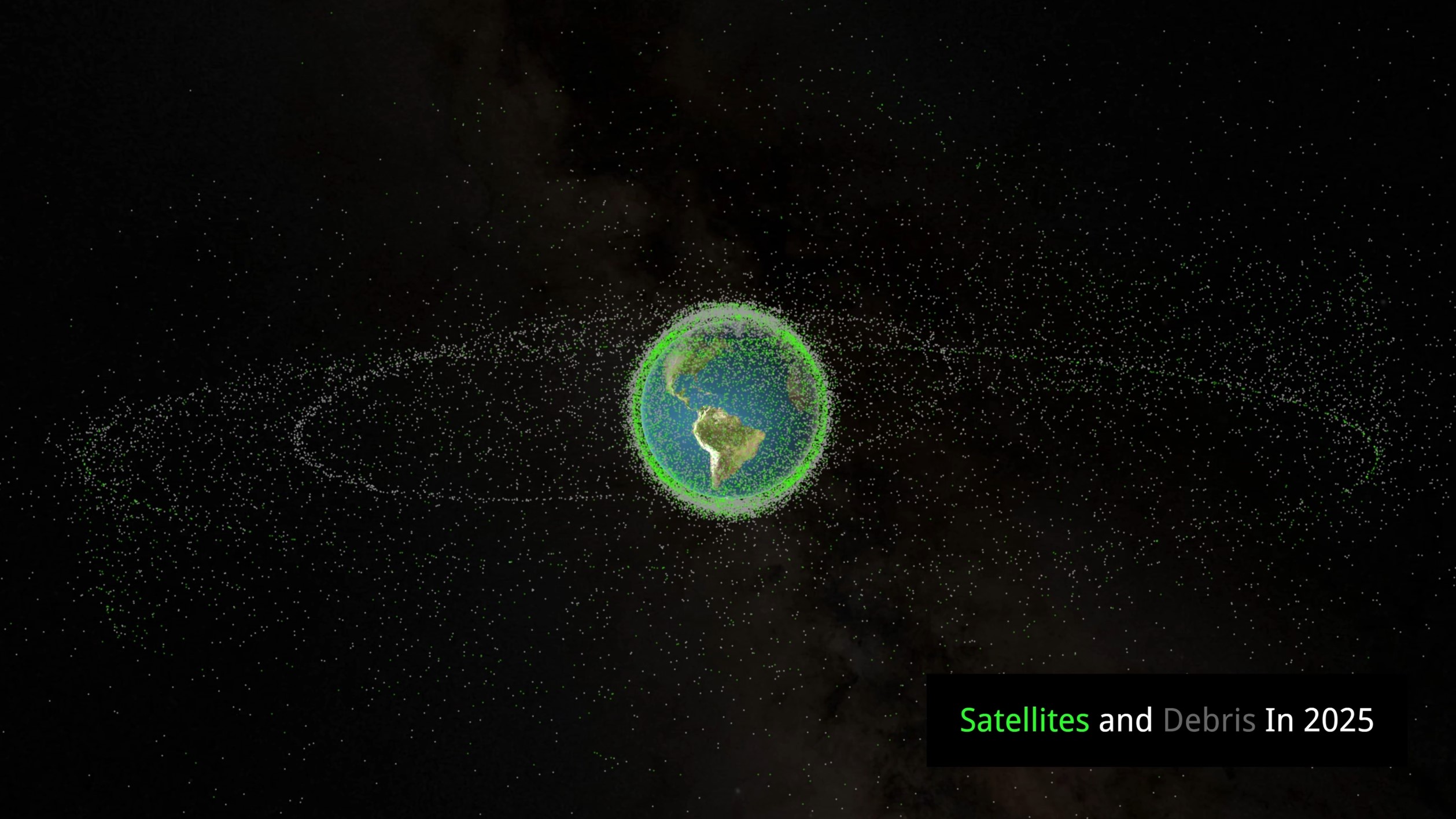

Today, as we enter an era of increasingly sophisticated commercial imagery satellites, the pioneering achievements of Discoverer 38 and the Corona program remain relevant. The fundamental challenges of orbit selection, camera design, and image retrieval that these early engineers solved created the foundation for modern satellite reconnaissance.

The legacy of Discoverer 38 reminds us that technological innovations often arrive cloaked in secrecy, their full impact only becoming clear decades later. The stereoscopic imaging capability first deployed sixty-three years ago today continues to influence how we observe our planet from space, whether for intelligence purposes, scientific research, or commercial applications.

As new generations of imaging satellites with ever-more-sophisticated sensors monitor our changing world, they build upon the engineering achievements of those early Corona missions—achievements that began with a rocket launch on a clear California morning and a satellite that officially did not exist.

Theodore Kruczek