· today in space history · 5 min read

The Day America Pioneered Polar Orbits

Sixty-six years ago, a Thor-Agena rocket thundered into the California sky carrying Discoverer 1, the first satellite attempt at polar orbit and the secret vanguard of Americas space reconnaissance program

As dusk settled over Vandenberg Air Force Base on February 28, 1959, a Thor-Agena A rocket stood poised on Launch Complex 75-3-4, silhouetted against the California coastline. At precisely 1:49 PM local time (21:49 GMT), its engines ignited with a thunderous roar, sending Discoverer 1 skyward on a trajectory unlike any satellite before it. Unlike previous spacecraft that circled the equator, this pioneering vehicle would attempt something entirely new: a path that would take it over Earth’s poles, revolutionizing both the science of space exploration and the art of intelligence gathering.

A Cover Story for Cold War Intelligence

While publicly presented as a scientific research satellite designed to test systems for eventual human spaceflight, Discoverer 1’s true purpose remained classified for decades. The satellite was actually the first mission in what would become the CORONA program, a joint initiative between the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), the U.S. Air Force, and the Central Intelligence Agency. This pioneering reconnaissance program aimed to replace vulnerable U-2 spy planes with orbital cameras that could photograph Soviet military installations from space.

“The overriding priority was to obtain reliable intelligence on Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile deployment,” explained a formerly classified CIA document later released to the public. “Without satellite reconnaissance, we would have had no direct means of determining the scale of the Soviet buildup.”

Engineering for the Unknown

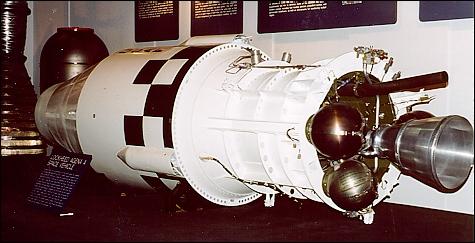

Discoverer 1 represented a marvel of aerospace engineering for its era. The cylindrical spacecraft measured 5.73 meters in length and 1.52 meters in diameter, with a lightweight magnesium casing designed to minimize weight while providing structural integrity. Unlike later missions in the series, this pathfinder carried no camera or film recovery capsule. Instead, its 18-kilogram payload consisted of sophisticated communications and telemetry equipment designed to prove the feasibility of controlled polar orbits.

The spacecraft included a high-frequency beacon transmitter for tracking and a radar beacon transponder that could receive command signals from the ground. Fifteen telemetry channels monitored approximately 100 different aspects of the satellite’s performance, gathering critical data that would inform future missions.

The Complex Path to Polar Orbit

Achieving a polar orbit required a completely different launch approach than the equatorial orbits used by previous satellites. Launching from Vandenberg Air Force Base on California’s coast provided a crucial safety advantage: the rocket could head south over open ocean, rather than populated areas, as it climbed toward space.

After the Thor first stage burned out at a velocity of 28,529 kilometers per hour, the rocket coasted to its intended orbital altitude. There, the Agena upper stage’s guidance system oriented the spacecraft using pneumatic nitrogen jets, achieving the precise attitude needed for orbital insertion. When the correct orientation was achieved, the second stage ignited, pushing Discoverer 1 toward its intended polar orbit.

A Mysterious Outcome

Almost immediately after launch, controllers encountered difficulties receiving signals from the satellite. Initially, the mission was declared a success, with the U.S. Air Force announcing that Discoverer 1 had achieved orbit. However, the satellite’s signals were only received intermittently during subsequent passes, raising questions about its true status.

Declassified documents later revealed significant uncertainty about the mission’s outcome. “Today, most people believe the Discoverer 1 landed somewhere near the South Pole,” stated a CIA retrospective report. The spacecraft likely failed to achieve a stable orbit and re-entered Earth’s atmosphere shortly after launch, though this was not publicly acknowledged at the time.

Legacy of Innovation

Despite the ambiguous outcome, Discoverer 1 pioneered crucial technologies and operational procedures that would enable successful reconnaissance missions. The launch marked the first flight test of the Lockheed Agena upper stage, which would become a workhorse for military and civilian space missions throughout the 1960s. The mission also established operational protocols for launching from Vandenberg, a site that would become America’s primary facility for polar orbit launches.

Most significantly, Discoverer 1 represented the first step in what would become one of America’s most successful intelligence programs. Over the next thirteen years, CORONA satellites would take more than 800,000 images covering 750 million square miles of territory, revolutionizing American understanding of Soviet military capabilities and dramatically reducing the “missile gap” fears that had driven defense policy.

From Secrecy to Scientific Advancement

While Discoverer 1’s military origins remained classified until 1995, the polar orbit capability it pioneered proved transformative for scientific and civilian applications. Today, most Earth observation satellites, weather monitoring systems, and many communications constellations rely on polar or near-polar orbits to achieve complete global coverage as Earth rotates beneath them.

“Polar orbits represent one of the most useful satellite paths we have,” explains aerospace historian Roger Launius. “The ability to systematically photograph the entire planet has transformed our understanding of Earth’s systems, from weather patterns to ocean currents to land use changes.”

Looking Forward

Sixty-six years after Discoverer 1’s pioneering flight, polar orbiting satellites have become essential tools for understanding our changing planet. Modern descendants of this early reconnaissance technology now monitor climate change, track natural disasters, and support global communications networks. The path pioneered by that first Thor-Agena launch from Vandenberg has become a standard trajectory for satellites requiring global coverage.

As we look to the future of Earth observation and planetary monitoring, the legacy of Discoverer 1 reminds us that technologies developed for national security often yield unexpected benefits for scientific progress and environmental protection. The satellite that secretly aimed to watch our geopolitical adversaries ultimately helped humanity better see and understand our shared planet, demonstrating how even the most clandestine space missions can ultimately serve the broader advancement of scientific knowledge.

Theodore Kruczek